Map 1: Toronto’s post-war apartment towers and rapid transit, overlaid with the wealthy ‘City #1’ (Grey) and intensification zones (Red).

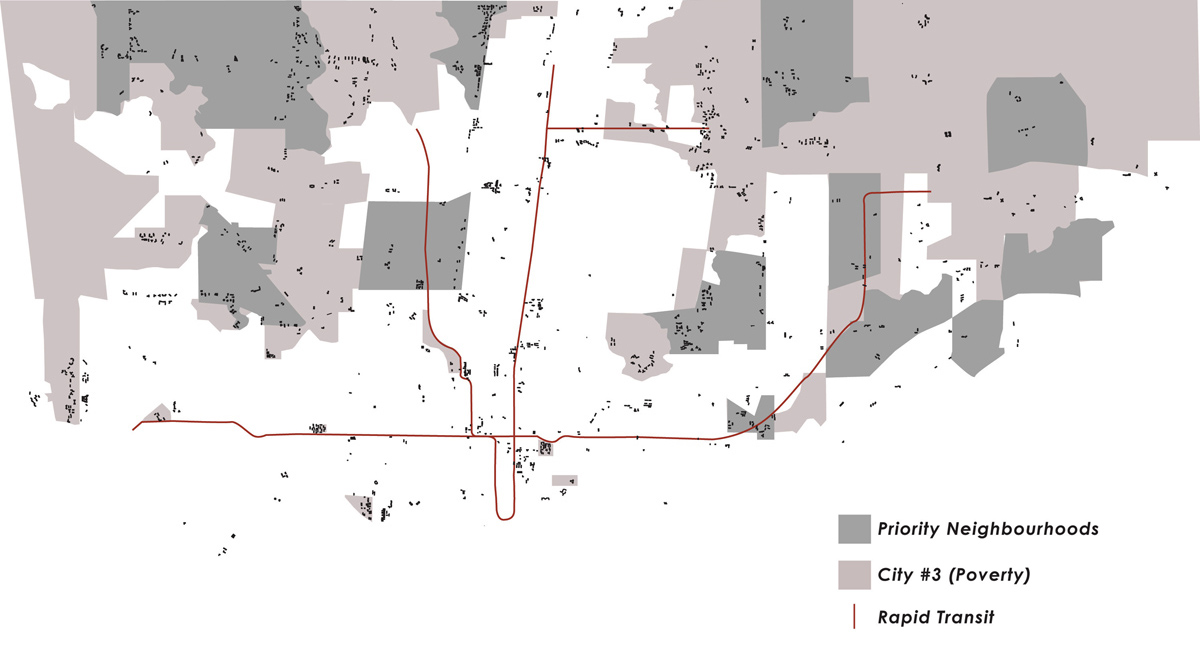

Map 2: Toronto’s post-war apartment towers and rapid transit, overlaid with the impoverished ‘City #3’ (Grey) and Priority Neighbourhoods (Dark Grey).

Toronto is quickly becoming a polarized city. New research out of the Centre for Urban and Community Studies at the University of Toronto has revealed startling trends related to changing income distribution patterns across the city.

Toronto in the 1960’s and 1970’s was mainly a middle-income city, with only a few pockets of overt wealth and poverty. Over the past twenty years however, that middle income group has fallen from 2/3’s to 1/3 of the city – creating a geographically divided, “3 cities” within Toronto. These can be loosely characterized as City #1, an area of concentrated wealth and gentrification (about 20% of Toronto); City #3, areas of concentrated poverty; and City #2, an in between average city, likely in the process of transition. City #2 and #3 each comprise about 40% of Toronto (as of 2001).

City #1 is generally located in historic neighbourhoods near the core, close to the best social, cultural and physical infrastructure, including rapid transit, and is the target of significant new private and public investment. In contrast, City 3, represents a growing number of neighbourhoods located in the “inner suburbs” built in the post-war boom, which currently suffer form lack of rapid transit, fewer social and community services, and little new investment. City #2 represents the average city, the shrinking middle-income group predicted to further erode into either City #1 or City #3, creating further polarization.

There is a striking correlation between aging tower neighbourhoods and City #3. While Toronto’s mid-century towers are located throughout all three cities of Toronto and represents a diversity of communities, they are undeniably tied to the challenges of increased poverty and inadequate services.As a first step, the City of Toronto has created series of programs to encourage investment and increased social services in “Priority Neighbourhoods”. Moving forward, how might the inherited high densities and underutilized open space found in apartment neighbourhoods themselves aid in the challenges of City #3?

With thoughtful incentives, apartment neighbourhoods provide a great opportunity to not only make environmental improvements to the City’s carbon footprint through building retrofits, but also respond to growing socio-economic challenges. With appropriate intervention responding to the needs and aspirations of residents and the community at large, apartment neighbourhoods could become the staging ground for service delivery, mixed-use developments at grade, new housing, markets, and even urban agriculture.

Allowed to evolve in response to new challenges, these priority neighbourhoods could be the catalyst in creating a more balanced and equitable Toronto.

Written by David Hulchanski, Graeme Stewart, and Michael McClelland. This article first appeared in Novæ Res Urbis (NRU). ERA is contributing articles to NRU on a weekly basis about the Toronto Tower Renewal project.

J. David Hulchanski is the Director of the Centre for Urban and Community Studies at the University of Toronto, and the author of “Three Cities Within Toronto, Income Polarization 1970 – 2000”